BFI Film on Film Festival Roundup

Last week I attended BFI’s first Film on Film Festival in London.

Between June 8-11, all the screening rooms at the BFI Southbank showed films projected on different types of film including 35mm, 70mm, 16mm, and the first public screenings of films on 35mm nitrate prints in the UK for over a decade. Four days relying on professional projectionists to screen films on the big screen just like how it used to be done before the introduction of digital cinema projectors in the late 1990s, a collective appreciation of film prints and their histories, and a new experience for people who may have never attended a film screening on actual film.

But most importantly, I think a festival like this is to celebrate and appreciate the heritage of cinema and an entry point to anyone new to it. There were very generous efforts of knowledge sharing, from the thoughtful film introductions, program notes and free talks and workshops.

Rare and new prints from BFI’s film collection were screened during those four days. A number of films on print are screened throughout the year, but not as much as in the past based on what I’ve heard from a few of my cinephile friends in London, especially during the big retrospectives.

There are still a few cinemas in London and across the UK that have film projectors and regularly screen films on 35mm, but with the current state of commercial cinema especially out of Hollywood and the infantilisation of films culture over the past couple of decades, plus online streaming that’s cultivated a very passive nature of viewing habits at home, there’s a need for institutions like the BFI to celebrate and show off its film collection, educate the public and engage them with cinema history and remind people why it is still important to go see a film on a big screen.

At the recent CineMAS film festival I curated, I was frequently asked where can films shown at the festival be found online because some people couldn’t attend and expected the films are / will be available online. The past three years have truly created a false sense of accessibility.

Additionally, living in a country where the bar isn’t very high with how films are programmed and presented, and is very behind when it comes to an appreciation on film and cinema heritage from an institutional level, I rely on film institutions elsewhere to keep the lights on so I can travel every opportunity I get to satisfy my cinephelia needs. I nodded my head in agreement when I read this line from a tweet by Gary Couzens, “Never dismiss the power of cineastes with disposable income.”

I watched 14 films at the festival, the oldest was from 1932 and the newest was a short film made this year. Each film had very thoughtful and informative introductions plus free printed programme notes (a favourite BFI ongoing tradition).

The projectionists were acknowledged by name and applauded before each screening, and before the screening of the three films on 35mm nitrate, Dom Simmons, BFI’s Head of Technical Services was on stage endearingly explaining the safety measures taken to project volatile nitrate prints. I’m sure I wasn’t the only one in the audience who developed a small crush on him that weekend.

This is was what I watched:

Day 1:

A Dog Called Discord (Mark Jenkin, 2023, 22min, 35mm)

Mildred Pierce (Michael Curtiz, 1945, 35mm)

Day 2:

Far and Away (Ron Howard, 1992, 70mm)

Louisiana Story (Robert J. Flaherty, 1948, 35mm)

Morvern Callar (Lynne Ramsay, 2002, 35mm)

Ash Wednesday (Larry Peerce, 1973, 35mm)

Day 3:

The Swimmer (Frank Perry, 1968, 35mm)

My Brilliant Career (Gillian Armstrong, 1979, 35mm)

Citizen Band (aka Handle with Care) (Jonathan Demme, 1977, 35mm)

Stella (Michael Cacoyannis, 1955, 35mm)

Day 4:

Service for Ladies (Alexander Korda, 1932, 35mm nitrate)

Blood and Sand (Rouben Mamoulian, 1941, 35mm nitrate)

No Way Out (Joseph L. Mankiewicz, 1950, 35mm nitrate)

Losing Ground (Kathleen Collins, 1982, 35mm)

The festival opened with A Dog Called Discord, a new short film by Mark Jenkin commissioned by the BFI followed by Mildred Pierce on a new 35mm print (and not on 35mm nitrate as promised because of a projector issue). We got over our disappointment soon enough though, the quality of the new print looked gorgeous and we were all fixated on one of the most emotionally tormented mothers in cinema.

Far and Way on 70mm (and my second cinema viewing since its release in 1992 in Dubai) was utterly enjoyable and a perfect choice for a Friday morning slot. The film is silly, “In my imagination, America is a wonderfully modern place” sounds outdated in present day context, but I was swept away by the film’s grandness and Enya’s Book of Days. I had a big grin on my face when it ended. But I also thought about how much older I am now, as are Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman.

A wish came true watching Morvern Callar in a cinema, my favourite film by Lynne Ramsay. We saw the original 2001 show print that was never screened before and it looked perfect.

Ash Wednesday from the BFI National Archive and “possibly the only surviving 35mm print in the UK” was a treat. Stand out moments for me - the black dress and the deep red velvet dress in two different dinner scenes worn by Elizabeth Taylor, and Helmut Berger with Elizabeth.

The Swimmer on a Technicolor dye-transfer 35mm print, and “unlikely to be screened again because of shrinkage” - I had seen this film once before at home a few years ago and was glad to finally be able to see it in a cinema.

A major discovery for me was Gillian Armstrong’s My Brilliant Career. We watched a new 35mm print, part of BFI’s “Keep Film on Film” initiative. I went in knowing nothing about the film and left thinking it is essential viewing for all young girls. “I can’t lose myself in somebody else’s life when I haven’t lived my own”.

Also, when a very young and very handsome Sam Neill appeared on the screen, I gasped.

The Badlands Collective presented Jonathan Demme’s underseen Citizen Band (aka Handle with Care) on a vintage 35mm print. It is about family, community, connections and misinformation, and relatable to the current times. “Everybody in this town is somebody they’re not supposed to be!” I’m always happy when I can attend a Badlands Collective screening, and this was my 3rd.

It was the first time I experienced watching films on 35mm nitrate, two black and white films, Service for Ladies (Alexander Korda, 1932) and No Way Out (Joseph L. Mankiewicz, 1950), and a rich and luminous coloured print of Blood and Sand (Rouben Mamoulian, 1941).

It was also my first time back at the BFI since 2019 and was definitely worth getting on a plane to attend.

It was great to watch films presented with care and to be surrounded by well mannered audiences (young and old) that respect cinema.

The photos below are of the cinema curtains in NFT1 and NFT2 where I spent most of my time. Waiting for the cinema curtain to open before the start of a film is like a slow unwrapping of a gift.

I leave you with an extract from the introduction essay in the festival programme booklet written by Robin Baker, the Programme Director of BFI Film on Film Festival and Head curator. You can read the complete essay here:

Digital technologies have revolutionised the ways we access and restore films, and changed how films look. Digital projection looks brighter, its reproduction of film grain is buzzier and colours appear more vibrant. But digital can’t recreate the specific qualities of a projected print. A print can feel more relatable, more unpredictable. Like us, it will change over time, its ‘imperfections’ helping to convey the life it has led. And then there’s the whirr as a reel of film passes through the projector; the sound of a reel change and the flicker created as a shutter opens and closes multiple times a second. It’s almost imperceptible, but magical nonetheless.

The BFI National Archive’s curatorial team has selected a programme almost entirely from the national collection of film and television. We have used it as an excuse to highlight many underseen titles, a wide range of formats and some glorious prints. And if some occasionally appear less than perfect, they wear their scars with pride.

In many cases, you will be watching original release prints, providing a physical and emotional connection to audiences from the past.

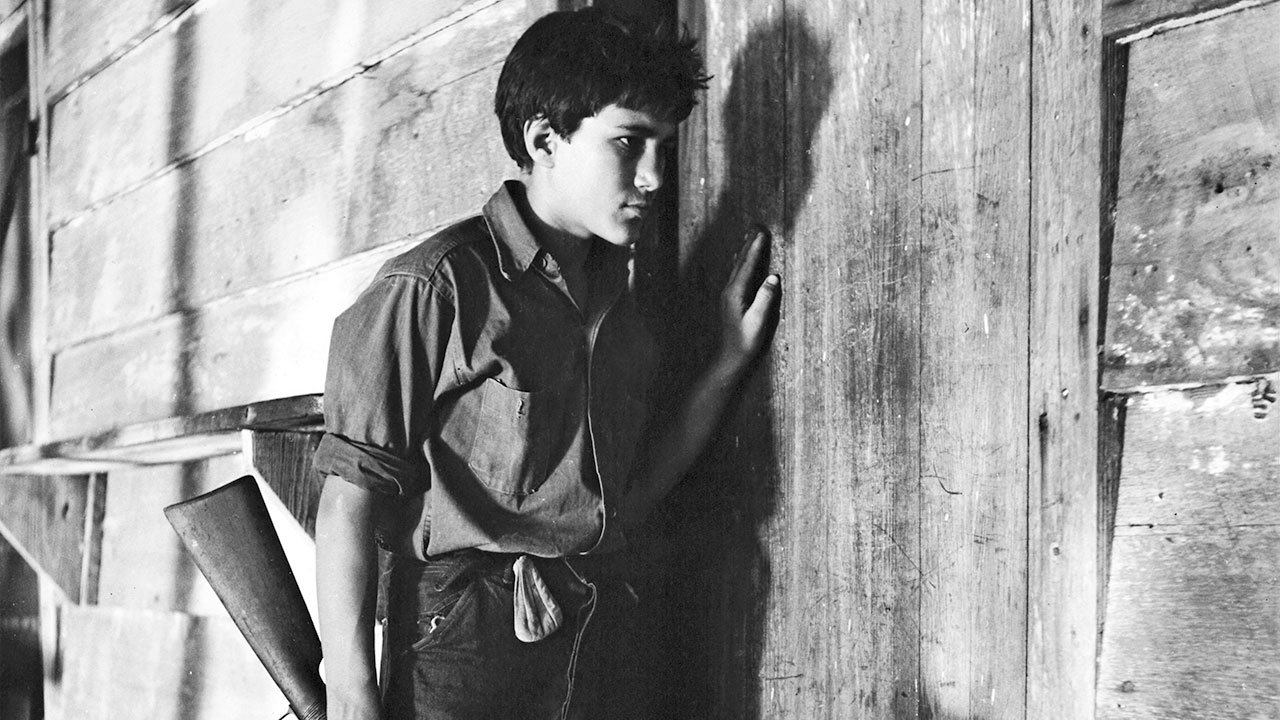

Handling 35mm film at the BFI National Archive (photo from BFI)